Most of this material is from Open Stax

Watch this introductory video

Viruses are diverse entities. They vary in their structure, their replication methods, and in their target hosts. Nearly all forms of life—from bacteria and archaea to eukaryotes such as plants, animals, and fungi—have viruses that infect them. While most biological diversity can be understood through evolutionary history, such as how species have adapted to conditions and environments, much about virus origins and evolution remains unknown.

Discovery and Detection

Viruses were first discovered after the development of a porcelain filter, called the Chamberland-Pasteur filter, which could remove all bacteria visible in the microscope from any liquid sample. In 1886, Adolph Meyer demonstrated that a disease of tobacco plants, tobacco mosaic disease, could be transferred from a diseased plant to a healthy one via liquid plant extracts. In 1892, Dmitri Ivanowski showed that this disease could be transmitted in this way even after the Chamberland-Pasteur filter had removed all viable bacteria from the extract. Still, it was many years before it was proven that these “filterable” infectious agents were not simply very small bacteria but were a new type of very small, disease-causing particle.

Virions, single virus particles, are very small, about 20–250 nanometers in diameter. These individual virus particles are the infectious form of a virus outside the host cell. Unlike bacteria (which are about 100-times larger), we cannot see viruses with a light microscope, with the exception of some large virions of the poxvirus family. It was not until the development of the electron microscope in the late 1930s that scientists got their first good view of the structure of the tobacco mosaic virus (TMV) ([link]) and other viruses (Figure). The surface structure of virions can be observed by both scanning and transmission electron microscopy, whereas the internal structures of the virus can only be observed in images from a transmission electron microscope. The use of these technologies has allowed for the discovery of many viruses of all types of living organisms. They were initially grouped by shared morphology. Later, groups of viruses were classified by the type of nucleic acid they contained, DNA or RNA, and whether their nucleic acid was single- or double-stranded. More recently, molecular analysis of viral replicative cycles has further refined their classification.

(credit a: modification of work by U.S. Dept. of Energy, Office of Science, LBL, PBD; credit b: modification of work by J.P. Nataro and S. Sears, unpub. data, CDC; scale-bar data from Matt Russell)

Evolution of Viruses

Although biologists have accumulated a significant amount of knowledge about how present-day viruses evolve, much less is known about how viruses originated in the first place. When exploring the evolutionary history of most organisms, scientists can look at fossil records and similar historic evidence. However, viruses do not fossilize, so researchers must conjecture by investigating how today’s viruses evolve and by using biochemical and genetic information to create speculative virus histories.

While most findings agree that viruses don’t have a single common ancestor, scholars have yet to find a single hypothesis about virus origins that is fully accepted in the field. One such hypothesis, called devolution or the regressive hypothesis, proposes to explain the origin of viruses by suggesting that viruses evolved from free-living cells. However, many components of how this process might have occurred are a mystery. A second hypothesis (called escapist or the progressive hypothesis) accounts for viruses having either an RNA or a DNA genome and suggests that viruses originated from RNA and DNA molecules that escaped from a host cell. A third hypothesis posits a system of self-replication similar to that of other self-replicating molecules, likely evolving alongside the cells they rely on as hosts; studies of some plant pathogens support this hypothesis.

As technology advances, scientists may develop and refine further hypotheses to explain the origin of viruses. The emerging field called virus molecular systematics attempts to do just that through comparisons of sequenced genetic material. These researchers hope to one day better understand the origin of viruses, a discovery that could lead to advances in the treatments for the ailments they produce.

Viral Morphology

Viruses are acellular, meaning they are biological entities that do not have a cellular structure. They therefore lack most of the components of cells, such as organelles, ribosomes, and the plasma membrane. A virion consists of a nucleic acid core, an outer protein coating or capsid, and sometimes an outer envelope made of protein and phospholipid membranes derived from the host cell. Viruses may also contain additional proteins, such as enzymes. The most obvious difference between members of viral families is their morphology, which is quite diverse. An interesting feature of viral complexity is that the complexity of the host does not correlate with the complexity of the virion. Some of the most complex virion structures are observed in bacteriophages, viruses that infect the simplest living organisms, bacteria.

Morphology

Viruses come in many shapes and sizes, but these are consistent and distinct for each viral family. All virions have a nucleic acid genome covered by a protective layer of proteins, called a capsid. The capsid is made up of protein subunits called capsomeres. Some viral capsids are simple polyhedral “spheres,” whereas others are quite complex in structure.

In general, the shapes of viruses are classified into four groups: filamentous, isometric (or icosahedral), enveloped, and head and tail. Filamentous viruses are long and cylindrical. Many plant viruses are filamentous, including TMV. Isometric viruses have shapes that are roughly spherical, such as poliovirus or herpesviruses. Enveloped viruses have membranes surrounding capsids. Animal viruses, such as HIV, are frequently enveloped. Head and tail viruses infect bacteria and have a head that is similar to icosahedral viruses and a tail shape like filamentous viruses.

Many viruses use some sort of glycoprotein to attach to their host cells via molecules on the cell called viral receptors (Figure). For these viruses, attachment is a requirement for later penetration of the cell membrane, so they can complete their replication inside the cell. The receptors that viruses use are molecules that are normally found on cell surfaces and have their own physiological functions. Viruses have simply evolved to make use of these molecules for their own replication. For example, HIV uses the CD4 molecule on T lymphocytes as one of its receptors. CD4 is a type of molecule called a cell adhesion molecule, which functions to keep different types of immune cells in close proximity to each other during the generation of a T lymphocyte immune response.

Among the most complex virions known, the T4 bacteriophage, which infects the Escherichia coli bacterium, has a tail structure that the virus uses to attach to host cells and a head structure that houses its DNA.

Adenovirus, a non-enveloped animal virus that causes respiratory illnesses in humans, uses glycoprotein spikes protruding from its capsomeres to attach to host cells. Non-enveloped viruses also include those that cause polio (poliovirus), plantar warts (papillomavirus), and hepatitis A (hepatitis A virus).

Enveloped virions like HIV, the causative agent in AIDS, consist of nucleic acid (RNA in the case of HIV) and capsid proteins surrounded by a phospholipid bilayer envelope and its associated proteins. Glycoproteins embedded in the viral envelope are used to attach to host cells. Other envelope proteins are the matrix proteins that stabilize the envelope and often play a role in the assembly of progeny virions. Chicken pox, influenza, and mumps are examples of diseases caused by viruses with envelopes. Because of the fragility of the envelope, non-enveloped viruses are more resistant to changes in temperature, pH, and some disinfectants than enveloped viruses.

Overall, the shape of the virion and the presence or absence of an envelope tell us little about what disease the virus may cause or what species it might infect, but they are still useful means to begin viral classification (Figure).

(credit “bacteriophage, adenovirus”: modification of work by NCBI, NIH; credit “HIV retrovirus”: modification of work by NIAID, NIH)

Which of the following statements about virus structure is true?

- All viruses are encased in a viral membrane.

- The capsomere is made up of small protein subunits called capsids.

- DNA is the genetic material in all viruses.

- Glycoproteins help the virus attach to the host cell.

Types of Nucleic Acid

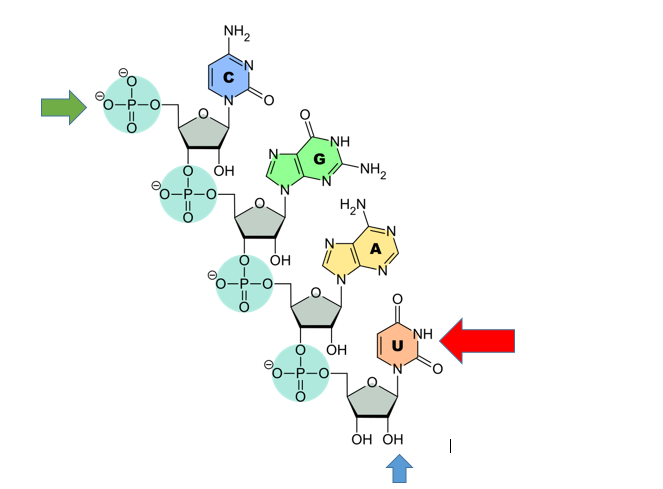

Unlike nearly all living organisms that use DNA as their genetic material, viruses may use either DNA or RNA as theirs. The virus core contains the genome or total genetic content of the virus. Viral genomes tend to be small, containing only those genes that encode proteins that the virus cannot get from the host cell. This genetic material may be single- or double-stranded. It may also be linear or circular. While most viruses contain a single nucleic acid, others have genomes that have several, which are called segments.

In DNA viruses, the viral DNA directs the host cell’s replication proteins to synthesize new copies of the viral genome and to transcribe and translate that genome into viral proteins. DNA viruses cause human diseases, such as chickenpox, hepatitis B, and some venereal diseases, like herpes and genital warts.

RNA viruses contain only RNA as their genetic material. To replicate their genomes in the host cell, the RNA viruses encode enzymes that can replicate RNA into DNA, which cannot be done by the host cell. These RNA polymerase enzymes are more likely to make copying errors than DNA polymerases, and therefore often make mistakes during transcription. For this reason, mutations in RNA viruses occur more frequently than in DNA viruses. This causes them to change and adapt more rapidly to their host. Human diseases caused by RNA viruses include hepatitis C, measles, and rabies.

Virus Classification

To understand the features shared among different groups of viruses, a classification scheme is necessary. As most viruses are not thought to have evolved from a common ancestor, however, the methods that scientists use to classify living things are not very useful. Biologists have used several classification systems in the past, based on the morphology and genetics of the different viruses. However, these earlier classification methods grouped viruses differently, based on which features of the virus they were using to classify them. The most commonly used classification method today is called the Baltimore classification scheme and is based on how messenger RNA (mRNA) is generated in each particular type of virus.

Baltimore Classification

The most commonly used system of virus classification was developed by Nobel Prize-winning biologist David Baltimore in the early 1970s. In addition to the differences in morphology and genetics mentioned above, the Baltimore classification scheme groups viruses according to how the mRNA is produced during the replicative cycle of the virus.

Group I viruses contain double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) as their genome. Their mRNA is produced by transcription in much the same way as with cellular DNA.

Group II viruses have single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) as their genome. They convert their single-stranded genomes into a dsDNA intermediate before transcription to mRNA can occur.

Group III viruses use dsRNA as their genome. The strands separate, and one of them is used as a template for the generation of mRNA using the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase encoded by the virus. Group IV viruses have ssRNA as their genome with a positive polarity. Positive polarity means that the genomic RNA can serve directly as mRNA. Intermediates of dsRNA, called replicative intermediates, are made in the process of copying the genomic RNA. Multiple, full-length RNA strands of negative polarity (complimentary to the positive-stranded genomic RNA) are formed from these intermediates, which may then serve as templates for the production of RNA with positive polarity, including both full-length genomic RNA and shorter viral mRNAs.

Coronavirus is a positive single strand RNA virus. When it infects a cell, the RNA is an mRNA which means that it can encode proteins. This RNA can be transcribed to make a negative strand RNA. The negative strand can not make proteins, but it can make more positive strands which can be put in viral particles or be used to make more protein.

Group V viruses contain ssRNA genomes with a negative polarity, meaning that their sequence is complementary to the mRNA. As with Group IV viruses, dsRNA intermediates are used to make copies of the genome and produce mRNA. In this case, the negative-stranded genome can be converted directly to mRNA. Additionally, full-length positive RNA strands are made to serve as templates for the production of the negative-stranded genome.

Group VI viruses have diploid (two copies) ssRNA genomes that must be converted, using the enzyme reverse transcriptase, to dsDNA; the dsDNA is then transported to the nucleus of the host cell and inserted into the host genome. Then, mRNA can be produced by transcription of the viral DNA that was integrated into the host genome. Group VII viruses have partial dsDNA genomes and make ssRNA intermediates that act as mRNA, but are also converted back into dsDNA genomes by reverse transcriptase, necessary for genome replication. The characteristics of each group in the Baltimore classification are summarized in Table with examples of each group.

| Baltimore Classification | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Group | Characteristics | Mode of mRNA Production | Example |

| I | Double-stranded DNA | mRNA is transcribed directly from the DNA template | Herpes simplex (herpesvirus) |

| II | Single-stranded DNA | DNA is converted to double-stranded form before RNA is transcribed | Canine parvovirus (parvovirus) |

| III | Double-stranded RNA | mRNA is transcribed from the RNA genome | Childhood gastroenteritis (rotavirus) |

| IV | Single stranded RNA (+) | Genome functions as mRNA | Common cold (pircornavirus) |

| V | Single stranded RNA (-) | mRNA is transcribed from the RNA genome | Rabies (rhabdovirus) |

| VI | Single stranded RNA viruses with reverse transcriptase | Reverse transcriptase makes DNA from the RNA genome; DNA is then incorporated in the host genome; mRNA is transcribed from the incorporated DNA | Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) |

| VII | Double stranded DNA viruses with reverse transcriptase | The viral genome is double-stranded DNA, but viral DNA is replicated through an RNA intermediate; the RNA may serve directly as mRNA or as a template to make mRNA

|

Hepatitis B virus (hepadnavirus) |

- Viruses are tiny, acellular entities that can usually only be seen with an electron microscope. Their genomes contain either DNA or RNA—never both—and they replicate using the replication proteins of a host cell. Viruses are diverse, infecting archaea, bacteria, fungi, plants, and animals. Viruses consist of a nucleic acid core surrounded by a protein capsid with or without an outer lipid envelope. The capsid shape, presence of an envelope, and core composition dictate some elements of the classification of viruses. The most commonly used classification method, the Baltimore classification, categorizes viruses based on how they produce their mRNA.