Originally, I was going to assign the open Stax chapters on this material, but I decided it was way too complicated.

So lets start with these videos. The first one is an analogy. One little thing triggers a bunch of events:

(Appropriate title,no?)

This video gives a broad overview of cell communication. We will focus on how it relates to cell division and cancer.

First remember that there are three parts to signalling, Reception, Transduction and Response.

For cell division, recall that there is a checkpoint a the G1/S boundary. In order for cells to advance to S, they need proteins called growth factors. For example, if you injure yourself platelets (a type of blood cell most known for clotting) releases a protein called Platelet Derived Growth Factor. This protein stimulates cells to divide to replace the dead ones.

Here is a video about hair growth factors (sorry, it is an ad, but it gets the point across)

Reception In cell division, the growth factor binds to a receptor. Two common types are Enzyme linked and G-protein linked. Both play roles in cell division control.

Here is an example showing an enzyme linked receptor from Open Stax

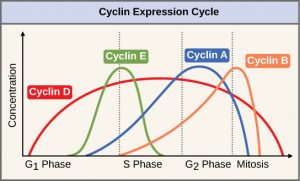

Response: These kinases activate enzymes and other proteins and lead to various results. One example is that some proteins go into the nucleus and tell cells to to make proteins like cyclins that trigger cell cycle events. A second example is a protein called Rb actively prevents cell division. Add a phosphate and the “brake” is released.

This is shown in the diagram from Open Stax

(2) When growth factors are present, a series of phosphorylation reactions occur, that end up adding a phosphate to Rb (Right) This releases E2F and the cell makes S phase cell cycle proteins.

Here is a review question relevant to Rb. Click and answer

Kinase Question

Now imagine that there is no Rb protein present at all. Click on the question below and answer it.

Rb Question

So that will help us transition into the last part of this lesson:

Cancer.

Rb stands for Retinoblastoma, a protein that was originally identified as being involved in in a rare childhood eye cancer.

This is the cancer connection:

Most people have 2 copies of the gene that makes this protein, one from each parent. During one’s lifespan, however, it is possible that both of these copies are damaged. If that happens, then Rb can not stop cells from going to S when they shouldn’t and excessive cell division occurs: Cancer. Note that while this gene was originally shown to be important in eye cancer, it is involved in many other types as well.

Some people have 1 only one functional gene, because they inherited a mutant from one of their parents. Their cells are OK with one copy, but it only takes one error to mutate the “good” copy. As a result, they have a very high rate of cancers.

Genes like Rb are called Tumor Suppressors. They have the following characteristics

(1) The normal function of the protein is to prevent the cell from dividing when it shouldn’t.

(2) When both copies of the gene are mutated to a form that does not function , cancer can result.

Here is another example from Open Stax, called P53. 50% of cancers have mutations in p53.

Mutated p53 genes have been identified in more than one-half of all human tumor cells. This discovery is not surprising in light of the multiple roles that the p53 protein plays at the G1 checkpoint. A cell with a faulty p53 may fail to detect errors present in the genomic DNA (Figure). Even if a partially functional p53 does identify the mutations, it may no longer be able to signal the necessary DNA repair enzymes. Either way, damaged DNA will remain uncorrected. At this point, a functional p53 will deem the cell unsalvageable and trigger programmed cell death (apoptosis). The damaged version of p53 found in cancer cells, however, cannot trigger apoptosis.

A normal cell will respond to DNA damage by fixing the damage, and if the damage is too severe, the cell will die by apoptosis. (Kill the cell, spare the organism)A cell lacking the P53 gene will not repair damaged DNA and it will allow abnormal cells to keep dividing. This can lead to cancer.

In some cancers (notably some forms of breast cancer), the receptor (because of a mutation) no longer needs the growth factor (The signalling molecule in red) to bind to the receptor to be active. This sets off the chain of events that leads to uncontrolled cell division.This cases illustrates some general principles of activated oncogenes (compare to tumor suppressors)

In some cancers (notably some forms of breast cancer), the receptor (because of a mutation) no longer needs the growth factor (The signalling molecule in red) to bind to the receptor to be active. This sets off the chain of events that leads to uncontrolled cell division.This cases illustrates some general principles of activated oncogenes (compare to tumor suppressors)(2) Only 1 copy of the gene has to be mutated

(3) They are rarely, if ever, inherited from parents.

Now answer this question (click on the link)

Here is some good news about cancer therapy.

Emily was one of the first to have this therapy, but now it is more widely. Former President Jimmy Carter, who is over 90 was successfully treated in this manner: